Unlike much of the world the United States has never had a royal family (except for Hawaii) or a class of nobles or titled aristocrats. Founding fathers such as George Washington, James Madison and Thomas Jefferson may have lived on big estates like English squires but they were never addressed as the Duke of Virginia or the Earl of Charlottesville. Like you and me they were commoners. Many Americans believe that the Kennedys are the closest thing to royalty in the U.S. However, there is another family that would have a better claim. The Livingstons of New York have not only lived like aristocrats since the 17th Century but have produced signers of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, Presidents, diplomats, members of congress and cabinet secretaries and have had a long and continuing influence on political life in the U.S. This post presents a brief history of the Livingstons and some of the country estates and mansions they built which for the most part still exist today.

The Livingston experience in America started in 1674 when 21 year old Robert Livingston arrived in Boston after having lived in the Netherlands with his Scottish parents. His father, the Reverend John Livingston, was banished from Great Britain in 1662 for not pledging loyalty to the recently enthroned King Charles II in the aftermath of the English Civil War. The Livingstons settled in Rotterdam where young Robert studied commerce and became fluent in Dutch. These skills served Robert well in the new world when he settled in Albany, New York which had recently been part of the Dutch colony of New Netherlands and where the power elite was still mostly composed of Dutch traders and landowners. One of these landowners was Nicholas Van Rensselaer who controlled the 700,000 acre Rensselaerwyck manor in the Hudson River Valley (roughly between Albany and Kindershook). Nicholas took a liking to the enterprising scotsman and appointed him as his secretary and as “Indian agent” on the manor. Within a couple of years Nicholas died and Robert married his widow, the brilliant and hard-charging Alida Schuyler of the influential Schuyler family. Together this power couple took charge over the commerce and politics of Albany and the Hudson River valley. In addition to managing extensive real estate holdings, the Livingstons financed slave trading and high seas piracy and Robert served in the Provincial Assembly of New York for many years.

In 1686, Robert and Alida received a land grant of 160,000 acres on the left bank of the Hudson (roughly the southern third of today’s Columbia County) and the Livingston Manor was born. Contrary to popular belief, a manor was not a house but a unit of land and a political subdivision that was owned by a private individual. Manors were the prevailing form of land ownership and political subdivision in Europe at the time and the system was introduced to French, Dutch, Spanish and British colonies in North America in the 17th century. Manors were usually granted to favored individuals that demonstrated great administrative and commercial abilities with the blessing of whichever king was reigning back in England. Often times the owner of a manor in North America was the second-born son of a manorial lord in the old country where the first-born son would inherit the entire estate, a system known as primogeniture that still exists today in the U.K. although now daughters can inherit as well. George Washington’s estate, Mount Vernon, and Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello were manorial-type estates originally granted by colonial governors .

The owners of manors, usually referred to as a lord (British), patroon (Dutch), seigneur (French) or a don (colonial-era California), were granted extensive civil, judicial and governance powers over their manorial lands. The lord of a manor was in effect the landlord, governor, mayor and judge for those who lived on the manor. In return, the lord was expected by the sovereign or their colonial representative to govern competently, make the land prosperous, collect taxes and rents and settle disputes. Owners of manors would typically build a nice house on their property from which to administer the manor and this became known as the “manor house.” Many famous stately homes in the U.K. started out as manor houses and the term has come to be equated with any large, classically designed house whether or not it had anything to do with an actual manor. Interestingly, manor houses were not particularly exclusive or private in centuries past and manor tenants would often eat their meals and party on a daily basis with the lord in the house itself.

Manorial lands were farmed by tenant farmers who paid rents to the lord of the manor in the form of cash, crops or labor. Tenancies would usually pass from generation to generation pretty much tying the tenants to the land. Being a tenant on a manor was better than being a slave but your options and opportunities were still limited. Although it sounds harsh by today’s standards, manorial systems of governance made sense back in the day when central governments were relatively weak and communication and transportation was difficult and arduous.

Manorial systems slowly died out in Europe and North America as citizens demanded more rights and economic autonomy but remnants of the manor system still exist today. Manorial estates still predominate today in England with some dating back to the 16th century when King Henry VIII confiscated all the lands owned by the Catholic Church (which was most of England) and divvied it out to his favorite courtiers. The last manorial rents in Quebec were paid as late as 1970. To the present day some homeowners in Maryland still pay “ground rent” twice a year to some landlord, a relic of the days when Maryland was the domain of the colonial landowner and governor, the Baron Baltimore. (The 6th and final Baron Baltimore who ruled the colony before the British were kicked out actually never set foot in Maryland and reputedly spent all his income on drugs and prostitutes).

The Livingston Manor was largely settled by German refugees (hence the present-day town of Germantown in Columbia County). At its peak, the manor covered 700,000 acres. Robert (the Elder) and Alida Livingston had nine children and passed away in 1728 and 1727 respectively. Unlike in England where manorial estates were passed intact to first-born sons, the Livingston Manor was divided between his third and fourth sons, Philip and Robert. Robert the Younger founded the Clermont Manor, site of the Clermont mansion (shown above), on a 13,000 acre parcel carved out of the larger manor. Philip became the Lord of Livingston manor and he and his wife, Catherine, had 11 children including signers of the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution. Philip’s oldest son, yet another Robert, inherited Livingston Manor in 1749 but upon his death in 1790 the estate was divided among his five sons (which included another Robert) and a son-in-law.

The demise of the Livingston Manor as a viable real estate business was sealed during the “Anti-Rent Wars” of the 1840s. As the Livingston estate was subdivided among various heirs a problem arose as the ratio of rent-paying tenants to Livingston family landlords decreased. Like other manorial landlords who found themselves in the same boat, the Livingstons responded by becoming more aggressive about collecting delinquent rents and cracking down on unpermitted logging and mining. Manor tenants, emboldened by the new ideas of Jacksonian democracy, revolted against the landlord-tenant system and worked through the courts, the state legislature and used a fair amount of violence to abolish the semi-feudal system which predominated in New York. By 1850 the manor system was all but dead.

The Livingston lands, now not so lucrative as they had been, continued to be divided among heirs over the decades or were sold off. It was fairly common for Livingstons to marry cousins or in-laws to try and keep the ancestral lands within the family but over time most of the historic Livingston Manor passed out of family ownership. However, remnants of the estate are still owned by Livingston descendants in the present day.

Livingston descendants have had prominent roles in the political, social and artistic spheres in the United States right up to the present day. Descendants include Eleanor Roosevelt, David Crosby, founder and guitarist of Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young, and actors Jane Wyatt and Montgomery Clift. President George H. W. Bush was a 10th generation descendant of Lord Robert the Elder. The Livingstons linked up with the Astor family in 1818 when a Livingston married the son of John Jacob Astor (America’s first multi-millionaire and New York City slumlord). Their daughter-in-law was Caroline Astor “The Mrs. Astor” who invented social snobbery in America with her list of the 400 people it was deemed acceptable to invite to parties. The Livingstons also linked up through marriage with other prominent New York landlord dynasties such as the Van Rensselaers (owners of the Rennselaerwyck Manor), Van Cortlandts, Goelets and Schermerhorns and also had links to the Roosevelt and the Phipps family that gained their fortune from Carnegie Steel (later U.S. Steel). There is even a Livingston link (by marriage, not blood) with the Vanderbilt family.

The Livingstons built 20-30 mansions (depending on how you define a mansion) along the Hudson River in Columbia and Dutchess counties over the decades. Most of these still exist although most were sold out of the family over the years. The following paragraphs describe ten of the more notable or architecturally distinguished homes.

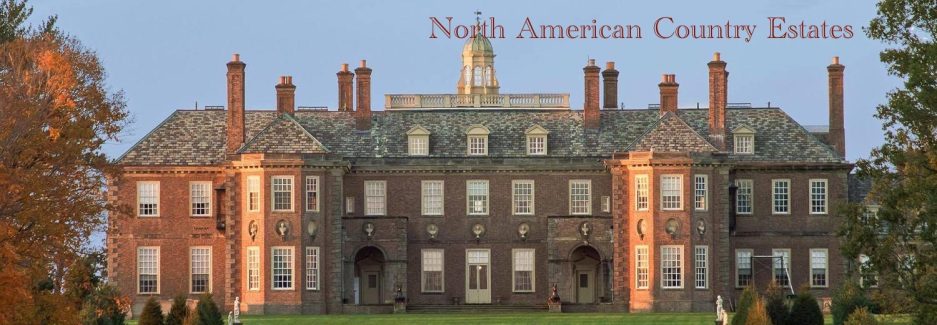

Clermont

Robert Livingston the Younger was the third son of the original Lord of Livingston Manor. He was educated in Scotland and England and briefly practiced law in Albany before returning to the Hudson Valley to help manage the manor. Upon the death of his father in 1728, he inherited a 13,000 acre chunk of the Livingston Manor south of the present day town of Germantown. He named his estate Clare (“Clear”) Mount because of the fine view of the Catskill Mountains from his picturesque home overlooking the river. Robert the Younger expanded his estate south into Dutchess County and across the river during his tenure and by the time he died in 1775 the estate amounted to 600,000 acres. Clermont passed to his son, another Robert, who was referred to as “Judge Livingston” but the Judge died a few months later and the estate was then managed by his widow, Margaret Beekman Livingston, for the next several years. In 1777 the British army sailed up the Hudson River burning and pillaging as they went and burned Clare Mount house down as punishment for the Livingston family’s support of the American Revolution. Margaret had the house rebuilt to its present form by 1782 and renamed the house and estate Clermont (French for Clear Mountain). Her oldest son, yet another Robert, was known as “The Chancellor” in reference to the high judicial office he held in New York State. The Chancellor was one of five founding fathers who drafted the Declaration of Independence (although it was his cousin Philip who signed it) and administered the first oath of office to the new President, George Washington. He served as Minister to France under President Thomas Jefferson and in that role negotiated the Louisiana Purchase with the Government of Napoleon Bonaparte. In his spare time he was a freemason and experimented with methods of raising sheep. One of the Chancellor’s great great great granddaughters was Eleanor Roosevelt. The Chancellor’s descendants continued to live at Clermont right up to 1962 when the last of the Clermont Livingstons, Alice Delafield Clarkson Livingston, deeded the estate to the State of New York. It is now known as Clermont State Historic Site and can be visited by the public to see the house as it was furnished in the early 20th century. Click here for more information about Clermont and how to visit this fascinating and historic home.

Montgomery Place

Montgomery Place dates back to 1805 and was built by Janet Livingston Montgomery and named in honor of her husband, Richard Montgomery, a general in the Continental Army fighting against the British in the American Revolution and who was killed during an unsuccessful invasion of Quebec. Janet’s mother was Margaret Beekman Livingston of Clermont. The house was inherited by Janet’s brother, Edward Livingston in 1828. Edward was a U. S. Senator representing Louisiana, Secretary of State and Minister to France under President Andrew Jackson and also a Mayor of New York City. The house stayed in the Livingston family until 1986 when it was sold to a non-profit organization and opened as a house museum after several years of renovation. In 2016, it was purchased by the adjacent Bard College and is now used as a classroom and special events center. The public can visit the property and explore the grounds and gardens. Click here for information on visiting Montgomery Place.

Callendar House

Callendar House is located near the town of Tivoli and was constructed in 1794 by Henry Gilbert Livingston who lived on the next estate northward along the river called The Pynes. Henry sold it the following year to a Livingston cousin. Originally called Sunning Hill, the house wasn’t dubbed Callendar House until 1860 when it was bought by Johnston Livingston after having been out of the family for a few decades. The name Callendar House was a nod to an ancestral Livingston family castle in Falkirk, Scotland that still exists. Johnston was an associate of banker J.P. Morgan and was one of the bankers who helped to mitigate financial disaster in the Panic of 1907. He was also one of the founders of both Wells Fargo Bank and American Express. Johnston’s descendants continued to live at Callendar House until 1976 when the house was put up for auction. Callendar House was then owned by a Swiss investment banker named Jean de Castella and used as a horse breeding operation. The house is currently owned by a New York City couple that work in finance especially in the energy sector and is not open to the public. Incredibly, The Pynes, the estate next door, is still owned by Livingston family descendants to the present day.

Staatsburgh

The house that would eventually become today’s Staatsburgh was built in 1833 by Morgan Lewis and his wife Gertrude Livingston who was a daughter of Margaret Beekman and Judge Livingston of Clermont. Morgan’s father had been a signer of the Declaration of Independence and Morgan himself was the third Governor of New York State as well as a State legislator. The Lewis/Livingstons had originally bought the 334 acre estate in 1792 and built a colonial style house on the site. This first house was destroyed in 1832 in a fire deliberately set by a disgruntled tenant farmer and rebuilt in a greek revival style. Three generations of Livingstons later, Ruth Livingston and her husband, Ogden Mills, hired architects McKim, Mead and White to remodel and enlarge Staatsburgh in 1896 by essentially building the Beaux-Arts mansion that stands there today over and around the existing house. The Mills’ also had homes in California (where Ogden’s father made his fortune in the gold fields), Paris, New York City and Newport, Rhode Island. Staatsburgh was just their weekend place while they were staying in the City. Their son, Ogden Livingston Mills, inherited Staatsburgh in 1929. Ogden Jr. was the U.S. Secretary of the Treasury when the Great Depression started and he convinced President Herbert Hoover to respond with tax increases and fiscal austerity which, as it turned out, made the depression even worse. Ogden’s sister, Gladys Mills Phipps, inherited Staatsburgh in 1937 but soon afterwards donated the estate, since expanded to 1,600 acres, to the State of New York for use as a state park. Unfortunately, the State failed to properly maintain Staatsburgh and the house deteriorated over the ensuing decades. It wasn’t until just recently that a concerted effort was made to try and rehabilitate the house. Part of the problem is that the 1896 construction was done in a very slipshod manner and the consequences have magnified over the years. Staatsburgh is open to the public and while the exterior of the house is in marginal condition the interior rooms are extravagantly furnished and show the house in all of its gilded age glory. For more information on Staatsburgh including how to visit, click here. Another house designed by McKim, Mead and White is a few miles south in Hyde Park, the Vanderbilt mansion – click here for more.

Teviotdale

Teviotdale was designed and built in 1774 by Walter Livingston, the sixth child of Robert Livingston, the third and final Lord of Livingston Manor. Teviotdale is located southeast of the town of Linlithgo and, unlike most of the Livingston homes, is well inland from the Hudson River. Walter married his cousin, Cornelia Schuyler, who herself was related to Alida Schuyler who founded the Livingston Manor with Robert the Elder. As mentioned previously, marrying cousins and in-laws was one way the Livingstons tried to keep the family real estate business intact. Walter and Cornelia had six children and the youngest, Harriet Livingston, married Robert Fulton, in 1808. Fulton was the inventor of the steamboat (christened the Clermont in honor of the family who helped finance the project). Tragically, Robert died of pneumonia seven years later after falling through ice into the frozen Hudson River while trying to rescue his attorney. It may not have been the happiest of marriages anyway as Fulton was not only obsessively busy with inventing but was also bisexual and what we would call polyamorous today. He tried to coax Harriet into polyamorous adventures but she declined. After Robert died Harriet moved into Teviotdale with her four children. Fulton had made good money from his boat inventions and between this legacy and some Livingston money Harriet was a wealthy widow. Unfortunately this situation attracted fortune hunters and a particularly bad one caught the eye of Harriet. She married Englishman, Charles Dale, in 1816 and within a few years he had burned through her inheritance including mortgaging and then losing Teviotdale through foreclosure. Teviotdale was sold to one of the house servants, Christian Cooper, and it remained in the Cooper family until it was bought by a Livingston descendant in 1927. Sadly, the house was abandoned in 1945 and largely forgotten until 1969 when it was bought and restored by interior designer Harrison Cultra and his partner Richard Barker. Upon the death of Barker in 1988, Teviotdale was willed to their friend, Victor Cornelius, a public finance specialist, who still owns it today. Mr. Cornelius has not only continued the restoration but has also bought surrounding properties to bring the estate closer to its historical extent. Teviotdale is a private home and not open to the public.

Rokeby

Rokeby is located north of Rhinebeck in a large area of woods and country estates that also include Edgewater, Sylvania and Steen Valetje, all Livingston homes covered in this post. The country estate that would become Rokeby was carved out of Clermont in 1800 after the death of Clermont’s Margaret Beekman Livingston for her daughter, Alida. Alida would marry John Armstrong in 1789. Armstrong was a U.S. Senator representing New York and Secretary of War and Minister to France (like an ambassador) under President James Madison. Armstrong had also been a member of the Continental Congress, the precursor to what we now call the U.S. Congress. He is the only member of the Continental Congress (which included most of the founding fathers of the United States) who lived long enough to be photographed. John and Alida completed Rokeby in 1815 originally calling it La Bergerie which means “sheepfold” in French and refers to the merino sheep which the Armstrong/Livingstons raised at the estate, a gift from Napoleon Bonaparte. John and Alida’s fifth child was Margaret Rebecca Armstrong who married William Backhouse Astor Sr., the son of John Jacob Astor, thereby linking the two most influential and wealthiest families in the U.S. during the early 19th century. William Astor bought La Bergerie from his father-in-law in 1836 and Margaret renamed it Rokeby after a fictional location in Scotland from a Sir Walter Scott poem.

William and Margaret’s granddaughter, Margaret “Maddie” Astor Ward, married John Winthrop Chanler in 1862. Chanler was a lawyer and member of the Winthrop family who settled Massachusetts in the 17th century. He served in Congress for seven years representing New York. John and Maddie had 11 children with eight living to adulthood. Tragically, both Maddie and John died of pneumonia within two years of each other while their children were still young. When they were orphaned the oldest, John, was just 15. The youngest was just three years old. Rokeby was left to the children, popularly known as the “Astor orphans,” and they each had a trust fund to finish their education and maintain an upper class lifestyle but they had minimal adult supervision while growing up. Thus began the strange and intriguing story of Rokeby as a sort of playhouse that continues to this day. The Astor family guarded the financial assets of the orphans and John Chanler’s cousin, Mary Marshall, became sort of a foster mother while the orphans tormented their tutors, goofed off, pulled pranks and roughhoused around the estate. By the turn of the century all the orphans had sold their share of Rokeby to the 8th orphan, Margaret Chanler, who started a dairy farm on the property with her husband, Richard Aldrich. The last surviving orphan, Alida Beekman Chanler, died in 1969. Alida was the last surviving member of “the 400,” the list of socially acceptable people according to one of her great aunts, Caroline Schermerhorn Astor, AKA “The Mrs. Astor.”

Margaret’s descendants still live at Rokeby. Whatever Astor money came down through inheritance is mostly gone and the house is in a state of genteel decay sustained by some organic farm income and hosting weddings. The house is also used as a retreat for visiting artists and writers. Incredibly, the house and the 400 acre estate is in its 338th year of Livingston/Astor family ownership. The house is not open to the general public but if you want to get married there this link has all the information. A couple of miles south of Rokeby is another Livingston/Astor house covered in this blog, Marienruh – click here for more on that.

Steen Valetje

Steen Valetje (small stony valley in Dutch) was carved out of the southernmost 100 acres of the Rokeby estate by William Backhouse Astor Sr. as a wedding gift for his daughter, Laura Eugenia Astor. Laura married Franklin Hughes Delano in 1844 and the house was completed seven years later. The Delano family had landed in North America with the same group of pilgrims who came over on the Mayflower (but on a different ship). Delano was involved in a shipping business before he married a Livingston/Astor and, afterwards, became active in managing the Astor real estate business. Franklin’s grand nephew was Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the 32nd President of the United States. Franklin and Laura Delano raised Norwegian ponies and Aberdeen Angus cattle on the estate and in later years spent most of their time in Monaco and Italy. Franklin died in 1893 and Laura gifted Steen Valetje to their nephew, Warren Delano IV, a coal company executive and a mentor to his nephew, FDR. Warren was also passionate about Norwegian horses but this hobby proved deadly when some of his horses took fright at a train and bolted into its path with Warren at the reins killing him instantly. His eldest son, Lyman Delano, inherited the estate and moved in with his wife, Leila, in 1922. They renamed it Mandara and kept it until Leila passed away in 1967. Thereafter, the estate had several owners and was renamed again to Atalanta. Currently, the estate, renamed yet again back to Steen Valetje is owned by Joseph Bae, the CEO of private equity giant Kohlberg Kravis Roberts and Co.

In addition to politics, the Delano family had wide ranging business interests in shipping, banking, railroads and drug dealing. Warren’s father, also named Warren and whose motto was “Just say yes,” made a fortune shipping Turkish opium to China in the 1840s. Another Delano, William Adams Delano, was a partner in the architecture firm of Delano and Aldrich responsible for many famous gilded age commissions in the first half of the 20th century including a significant Vanderbilt house covered in this blog, High Lawn, in the Berkshires. Click here for more on High Lawn.

Fox Hollow

Judge Livingston and Margaret Beekman Livingston of Clermont had ten children and five of them (or their descendants) built homes discussed in this post. Their third child, Margaret Livingston, married a surgeon named Thomas Tillotson who served in the American Revolution. Thomas and Margaret developed the Linwood estate overlooking the Hudson River south of Rhinebeck starting in 1788. Ten years later Tillotson subdivided Linwood creating the Glenburn estate to the east and deeded it to his 12 year old daughter, Janet. Glenburn was later enlarged by acquiring part of the neighboring Grasmere estate (another Livingston property). Janet’s granddaughter, Alice, would marry another Hudson Valley aristocrat, Tracy “Pup” Dows, and together they hired the society architect, Harrie Lindeberg, to design and build a colonial style mansion reminiscent of Mount Vernon in 1910 and called it Fox Hollow. Tracy and Alice lived a pleasant life as Hudson Valley gentry keeping busy with riding, sailing, dancing, drinking and traveling. They had three children, Stephen, Margaret and Deborah. Deborah, was an accomplished equestrian who trained at the Spanish Riding School in Vienna, home of the famous white Lipizzaner horses. She rode and trained alongside General George S. Patton prior to the Second World War and the general later pulled strings at the end of the war to place the Spanish Riding School under U.S. Army jurisdiction so it would not fall under the control of the Soviet Red Army which was occupying Vienna at the time.

Like many post-gilded age members of the idle class, the Dows’ spent more than they earned and they had to vacate Fox Hollow in 1930 and the house became a girls school. When Tracy Dows passed away in 1937 he left Fox Hollow to his three children. They subsequently sold the estate to their distant relative, Vincent Astor, who owned Ferncliff to the north of Rhinebeck. Deborah bought back 200 acres and established a horse farm, Southlands, that still exists as a foundation focusing on equestrian activities. Vincent Astor eventually sold Fox Hollow thus ending eight generations of family ownership dating back to Robert Livingston the Elder, the Lord of Livingston Manor. Today, Fox Hollow is a residential addiction treatment center so unless you have a drug problem it’s not possible to visit the house.

In an interesting footnote, Linwood was eventually bought by a brewer named Jacob Ruppert who owned the New York Yankees from 1915 until his death in 1939. Ruppert developed the intimidating Yankee teams of the 1920s and 30s including buying Babe Ruth from the Boston Red Sox and initiating the “Curse of the Bambino” that plagued Red Sox until 2004. He also built Yankee Stadium on land that had been owned by the Astor family in the Bronx.

Edgewater and Sylvania

Edgewater sits on a 250 acre estate right on the left bank of the Hudson (on the edge of the water) just west of Barrytown. The land under Edgewater house was a wedding gift from John Livingston (one of the children of Judge Livingston of Clermont) to his daughter, Margaretta, when she married in 1819. The Neo-classical house was built soon afterwards. When Margaretta’s husband and her father died in the 1850s she sold the house and moved to London. The new owner was a New York banker named Robert Donaldson and Edgewater stayed in his family until 1902. Edgewater was then bought by a member of the Astor family, Elizabeth Astor Winthrop Chanler, one of the “Astor orphans” who grew up at neighboring Rokeby, another Livingston/Astor estate (see above). Elizabeth and her husband, writer John Jay Chapman (whose great great grandfather was John Jay, the first Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court), used Edgewater house as a guest house and built another house called Sylvania on the hill behind Edgewater. Edgewater stayed in the Livingston/Astor/Chapman family until 1946. In 1950, Edgewater was bought by Gore Vidal, a writer and cultural zeitgeist during the 1960s and 1970s. Vidal was a step-brother, once removed, to Jacqueline Kennedy and was famous for defining the spirit of the age through his many witticisms that include:

“It is not enough to succeed. Others must fail”

“A narcissist is just someone who is better looking than you are”

“The United States was founded by the brightest people in the country. And we haven’t seen them since”

And finally…… “No good deed goes unpunished”

Gore Vidal was also famous for getting into very public feuds and lawsuits with other prominent writers and intellectuals such as Truman Capote (over allegations of drunkeness at the White House), conservative commentator William F. Buckley (where Buckley threatened to “sock him in the face”) and novelist Norman Mailer (about whom Vidal said “Once again, words failed Norman Mailer” after Mailer allegedly head butted Vidal backstage on the Dick Cavett Show).

By 1969, Edgewater had been whittled down to just 3 acres. It was bought that year by Richard Jenrette, an investment banker who founded Donaldson, Lufkin and Jenrette (DLJ) an influential Wall Street investment bank later acquired by Credit Suisse. Jenrette bought back some of the historical estate lands east of the house and restored the house itself including historically accurate furnishings. In 2018, Jenrette created the Classical American Homes Preservation Trust which currently owns Edgewater. Edgewater can be visited by the public a few days each month. Click here for more information about Edgewater and how to visit. Sylvania is a private home and not available for visits.

Much has been written about the Livingstons and their influence continues to reverberate through the cultural and political life of the United States right up to the present day. For more information about the family and their architectural heritage on the Hudson River, consider buying Life Along the Hudson: The Historic Country Estates of the Livingston Family available on Amazon here (not sponsored).