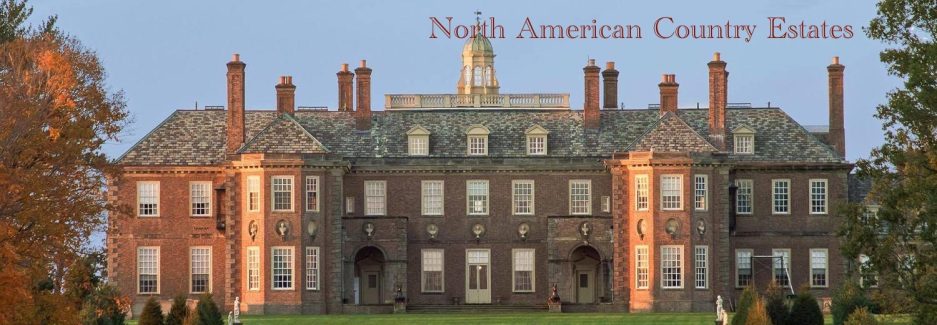

This is the Omega estate (AKA the Payne Estate) on the west bank of the Hudson River near Esopus, New York. The Beaux Arts style house was designed by Thomas Hastings of the New York architecture firm, Carrere & Hastings. The 42,000 square foot house was completed in 1911 and is sited on a 60 acre estate. The estate that eventually became Omega had three previous owners including John Jacob Astor III of the prominent Astor family and Omega was built on the site of an earlier house named Waldorf. Omega was the creation of Standard Oil executive Oliver Hazard Payne (1839-1917).

John D. Rockefeller, the founder of Standard Oil, had this tactic whereby he would calculate the value of a rival’s oil refinery assuming he had undercut their pricing and taken their market share and then Rockefeller would make the rival refiner an offer to buy their assets based on that assumed value. If the rival refused the offer, Rockefeller and the Standard Oil would simply undercut their prices, take their market share and drive them out of business. While this may seem similar to the choice that Latin American drug lords offer rivals and other troublemakers (“plata o plomo?” meaning “which do you want? silver or lead?”) it is actually quite humane given the rough and tumble business tactics that prevailed at the time. More often than not, the rival would take the offer and then be given a position within Standard Oil commensurate with their business acumen and degree of ruthlessness. Some of these one-time rivals became obscenely rich in their own right by joining the Standard Oil trust. Oliver Hazard Payne was one such rival who ended up doing just fine.

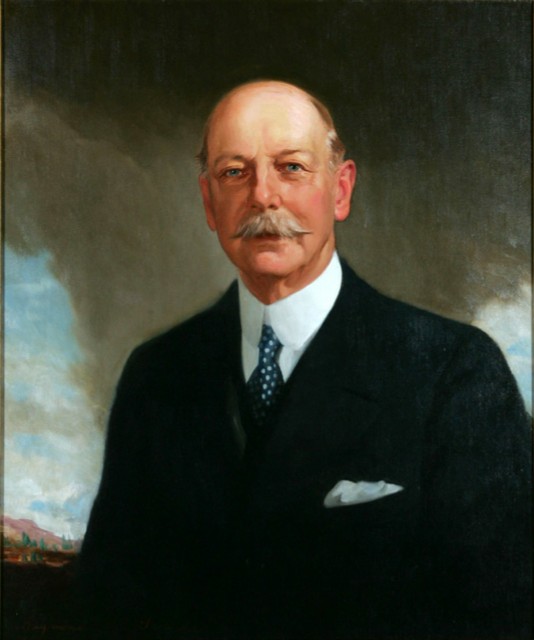

Oliver Hazard Payne was born into a politically prominent Ohio family and attended Phillips Academy Andover and Yale University. His mother was a relative of Navy admiral Oliver Hazard Perry who is famous for coining the phrase “Don’t give up the ship!” When the Civil War started, Oliver enlisted in the Army rather than avoiding conscription by paying someone to take his place as most wealthy young men were allowed to do. He was promoted to Colonel and commanded the 124th Ohio Infantry Regiment and served until the end of the war during which he was seriously wounded at the Battle of Chickamauga. After the war, Mr. Payne entered business starting up a refinery in Cleveland competing with Rockefeller’s Standard Oil. After selling out to Standard in 1872, Mr. Payne served as treasurer of the company and was also a company lobbyist. Back in those days, state and federal government in the United States was a hotbed of corruption, far worse than it is today. Bribery and kickbacks on behalf of gilded age corporate interests was pervasive and Mr. Payne was twice indicted on bribery charges but was not convicted. By the time he died in 1917 he was worth $190 million (several billion in today’s money).

Payne never married nor had any children and he left Omega to his nephew, Harry Payne Bingham. Mr. Bingham’s life was typical of second-generation gilded age industrial families (e.g., Corporate directorships, trusteeships, Park Avenue, NY Yacht Club, Palm Beach, Piping Rock Club, “scientific” yachting expeditions, Knickerbocker Club). Mr. Bingham got to use Omega for 16 years, a longer period of time than his uncle Oliver (who died only six years after its completion). After trying to sell Omega for several years, Mr. Bingham donated the property in 1933 to the New York Protestant Episcopal Mission Society which operated a convalescent home at the property. By 1937 the home had failed and in 1942 the estate was sold to Marist Brothers, a private liberal arts college and religious order in nearby Poughkeepsie for use as a high school for prospective brothers.

In 1986, the estate was purchased by businessman, Raymond Rich. Mr. Rich grew up in Iowa and started his working career in the engine room of a tramp freighter in 1930. After college he served in the Second World War in the pacific as a Marine. A born salesman and natural leader he was a professional CEO for most of his career and headed up several corporations. Mr. Rich loved nice homes and in addition to owning and extensively renovating Omega, he also owned castles in Scotland, Austria and France. He passed away in 2009 and left Omega, by now referred to as the Payne Estate, back to Marist College for use as the Raymond A. Rich Institute for Leadership Development.

For more information on Omega and the institute, click here and here. YouTube has a video showing scenes from the estate taken during the dedication of the Institute and can be seen here. Omega is almost directly across the Hudson River from another significant country estate covered in this blog, Hyde Park (click here for more).