No one builds 179,000 square foot houses anymore unless you live in the Persian Gulf and your job title is Sheik. But between the 16th century and 1914 hundreds were built, mostly in Western Europe. So what changed? The outbreak of World War One put a severe crimp on the finances of European aristocrats and the labor demands of industry made it increasingly difficult to retain the servants, house maids and gardeners necessary to maintain large homes on remote rural estates. When the soldiers came home after the war they were a lot more ambivalent about working for a social class that they blamed for starting the carnage. In the United States, there was never such a surplus of labor that made it feasible to staff a gigantic house. Being a household servant in the U.S. was also never considered a respectable vocation like it was in Europe and American gilded age plutocrats would often complain about the turnover and bad attitudes of their household staffs. The Great Depression brought any pretenses to being the lord of a great castle to a crashing halt. Even today with rampant income inequality in the U.S. and twelve digit tech fortunes hardly anyone builds houses such as were built during the so-called gilded age. Those that try usually end up with a giant fiasco rather than a gorgeous house. The Biltmore Estate in Asheville, North Carolina is famous for the very reason that there is nothing else like it in the U.S. It was finished in 1895 and nothing else like it has been built since. But even in the heyday of huge houses and chateaux, owners struggled to cover the expenses and keep these properties afloat. The financial pressures are even worse today with property taxes, estate taxes and income taxes. So how do homes like Biltmore and similar properties in Europe stay afloat?

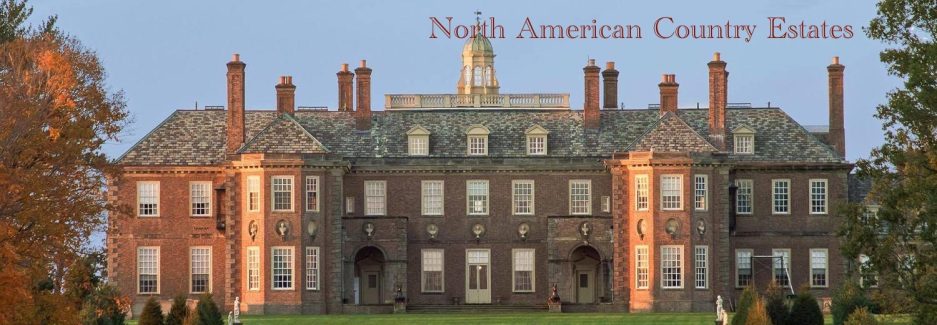

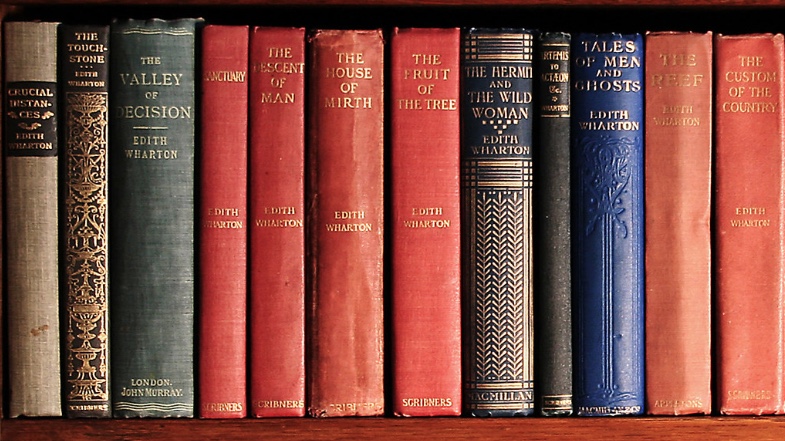

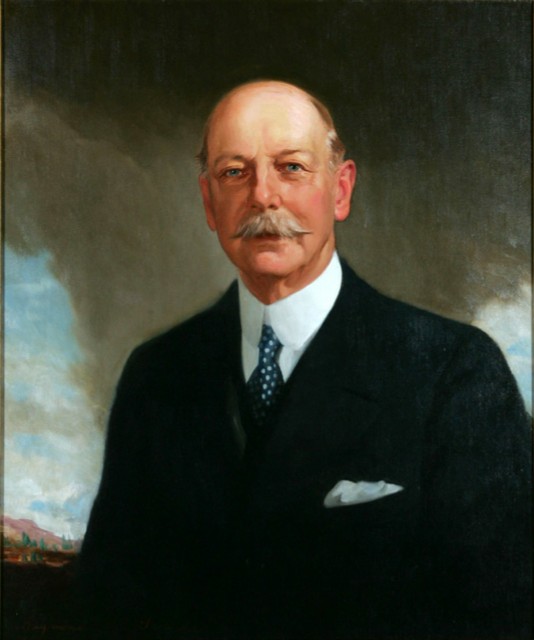

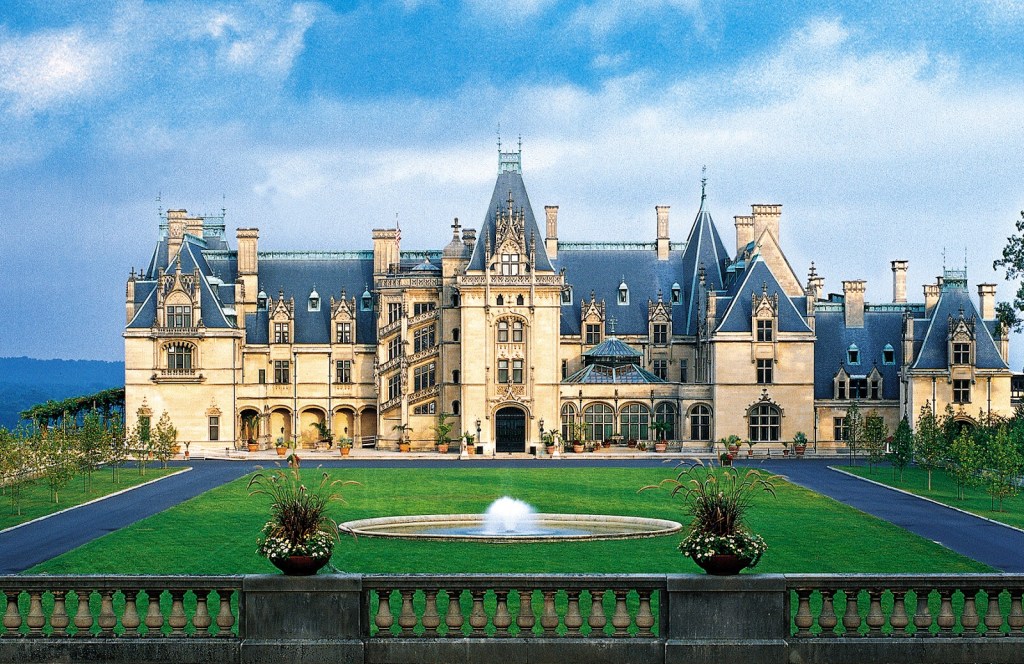

The story of Biltmore is well documented but here is a brief recap. It was the creation of George Washington Vanderbilt, a grandchild of Cornelius Vanderbilt, the 19th century railroad and steamship baron who started off with a single sailboat in Staten Island, New York and ended up with the largest fortune in the U.S. at the time, about $200 billion in today’s money. Illiterate, crass and profane, Vanderbilt was nevertheless a financial genius. He left most of his fortune to his eldest son, William Henry Vanderbilt, who doubled the value of his inheritance during his life. William Henry and his wife Maria had eight children and when William passed away in 1885 these kids took their inheritances and cut loose on houses, yachts and parties becoming the poster children of gilded age excess that is portrayed in movies, books and television. The youngest of these eight kids was George. His elder brothers ran the railroads while young George indulged in books and art. George also suffered from respiratory difficulties and in the 1880s at the suggestion of his doctors George started visiting Asheville for the warm, dry air and then started buying up small farms south of town. Much of this land had been overworked and was in poor condition and George had a vision of creating a modern version of a European feudal estate where the locals would live in villages that he created and work on farms and artisanal workshops on the estate while their children were educated in schools he built. The house was modeled after the chateaux that George had seen along the Loire valley in France and was designed by Richard Morris Hunt. The grounds were designed by Frederick Law Olmsted, generally regarded as the pioneer of landscape architecture in the U.S. At 179,000 square feet, Biltmore is the largest house ever built in North America.

By 1895 the house was completed and three years later George married Edith Stuyvesant Dresser, a descendant of the Dutch colonial governor of New Netherland (which eventually became New York). People have often commented on the lack of feminine touches in the design and decor of Biltmore and that is because it was built by a bachelor. Edith didn’t arrive on the scene until it was already built. George and Edith had three other homes in NYC and Maine. If you’re ever in Manhattan visit the Versace store on Fifth Avenue and you’ll be standing in George and Edith’s former townhome. Unfortunately, George’s vision of a self-supporting manorial estate didn’t pan out and after he died in 1914 at age 51 after a botched appendectomy his widow was forced to start selling parts of the estate to pay for taxes and maintenance. Part of the former estate is now a portion of the Pisgah National Forest and other parcels eventually became absorbed by the expanding city. The house started welcoming visitors as early as 1930 to help pay the bills.

George and Edith had one child, Cornelia Stuyvesant Vanderbilt. Cornelia grew up at Biltmore and after coming into her inheritance she married John Francis Amherst Cecil, a descendant of William Cecil, chief advisor to Queen Elizabeth I. Cornelia and John lived at Biltmore for a few years but Cornelia grew bored and restless and moved to Paris in 1934, dyed her hair pink, changed her name to Nilcha and divorced John. She never returned to the U.S. and married two more times before passing away in 1976. John and Cornelia had two sons, William A.V. Cecil and George H.V. Cecil, and after Cornelia bolted for Paris John stayed on at Biltmore and raised the boys until they left for school in England and Switzerland. John never remarried, managed the estate and lived in the bachelor wing of Biltmore until his death in 1954. Between 1956 and 1976 Biltmore, still owned by the absent Cornelia, stood empty but welcomed paying visitors.

When Cornelia died in 1976 William and George Cecil inherited the estate which included the house and a dairy business, a remnant of the artisanal industries that George Vanderbilt had started 80 years before. By this time Biltmore was an enormous white elephant that bled money. George, as the elder brother, got to pick what he wanted to inherit and he picked the dairy which at least turned a modest profit. William got stuck with the money-losing house. William essentially had a choice. Try to make Biltmore pay for itself, see if the federal or state government would take it on as a national park or house museum (as happened with Hyde Park his great uncle’s home in New York), try and sell it or demolish it.

As with Biltmore and the Cecil brothers, owners of huge historic houses in Western Europe also faced severe financial difficulties in the postwar era. The ravages of war, taxes to pay for the war, houses requisitioned for military use and then beat up and postwar societal attitudes that frowned upon architectural excess left owners with mostly bad choices. Some owners sold off their ancestral houses and lands that in many cases had been in the family for centuries or donated their houses to non-profits like the National Trust in England or to the local community in France. In England, hundreds of historic homes were demolished in the postwar era although most of the truly unique and attractive houses survived. Even though many historic homes had welcomed visitors for centuries the postwar era saw the emergence of the stately home industry where owners began to aggressively promote their properties as tourist attractions. Aristocratic landowners accustomed to the privacy that a large estate afforded became aggressive marketers and entrepreneurs opening up restaurants, gift shops, wedding chapels and the like. Today when you visit a historic home like Blenheim Palace or Chatsworth in England you will be rubbing shoulders with hundreds of visitors, wedding guests or business people hosting an event. Even with all this extra income the business of running a big historic house is typically little better than a break-even endeavor. But at least it keeps the house in the family and owners get to enjoy it during the off hours.

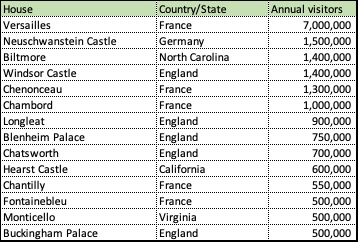

The Cecil brothers followed this model at Biltmore. George sold the dairy business and opened a winery and tasting room and parceled out much of the Biltmore agricultural land for residential and commercial development, hotels and shopping centers. Other parts of the estate have been developed for a wide range of tourism related uses. There is a mountain biking center, an equestrian center, a fitness center, a spa, several restaurants, a wedding venue, meeting facilities, banquet facilities, two hotels, a wide variety of retail shops, a nursery center, a shooting range, hiking trails, even a falconry center. And lest we forget there is also the Biltmore mansion that is open for tours starting at $70 per person and running as high as $130 per person at Christmas time when the house is decorated for the holidays. There are attractions for children as well but Biltmore has really become what some jokesters have dubbed “Disneyland for Adults.” Biltmore has become a major economic engine of Asheville and the major tourist attraction of western North Carolina. In the stately house industry Biltmore has become a model for not just financial sustainability but also a lucrative business for the Vanderbilt-Cecils, something that the original builder could never have imagined and wasn’t able to achieve. The chart below shows annual attendance figures for Biltmore and some of its peers in the stately and historic house industry. As shown, Biltmore is near the top of the table.

Of the fourteen houses in the table above, five are still used as homes today at least part of the year. Biltmore isn’t one of them. It hasn’t been lived in for nearly 70 years. Both of the Cecil brothers passed away by 2020 and the two businesses, Biltmore Company (which runs the house and most of the tourist attractions) and Biltmore Farms (the winery and property development arm), are now run by their children who live in smaller, more modern and manageable homes. While purists might decry the commercialism of Biltmore or similar properties in Western Europe it must be remembered that few of these houses were ever able to pay for themselves even at their peak in the 17th and 18th centuries. Their finances were pressured by factors beyond their owners control such as declining agricultural prices, wars, depressions, confiscation by communist regimes, death and taxes. Tourism has saved most historic houses especially the truly big ones like Biltmore or Blenheim Palace in England. Income from tourism pays for the upkeep and most of these houses have never looked better. Biltmore is just the extreme example of this trend and arguably the most successful.

For more on Vanderbilt houses be sure to click here for a post about Hyde Park, the creation of George Vanderbilt’s brother, Frederick, in New York as well as information on the mansion building binge of that generation of Vanderbilts. Or click here for a post about the stunning High Lawn house, uniquely the only gilded age Vanderbilt house that is still lived in by the family. For information about visiting Biltmore, click here. Double check your available credit card balance and have fun.