Anybody who has ever had a nickel to their name knows this house. Next to the White House, Monticello is undoubtedly the most famous house in North America. Thomas Jefferson was the third President of the United States, the second Governor of Virginia, President George Washington’s Secretary of State, author of the Declaration of Independence, founder of the University of Virginia, minister to the court of King Louis XVI and possibly one of the smartest people who ever lived. If you ever want to feel stupid, take a tour of the place that Jefferson called home for most of his life.

Jefferson’s reputation has taken a hit in recent years. Yes, he owned slaves. No, with a few exceptions, he did not free his slaves upon his death like Washington had (although Washington could have opted to not own slaves at all). He was particularly fond of one of his female slaves, Sally Hemmings. Sally was actually a half-sister of Jefferson’s wife, Martha (same father), and she was a house servant at Monticello. Martha passed away in 1782 and made Jefferson promise not to remarry. Subsequently, Sally accompanied Jefferson to Paris during his stint as Minister to France and eventually she became something like a surrogate wife to Jefferson. Over time, Sally bore six children by Jefferson starting when she was 16 years old. She and her four surviving children were all eventually freed from slavery.

Despite Jefferson’s association with slavery, the positive parts of his legacy live on. Jefferson, a polymath, was a world-class gardener, political scientist, gourmet, enlightenment philosopher and architect and spoke several languages. Although he denied the workers on his estate the basic legal and civil rights that he professed were inalienable and universal, his ideas were the foundation of future laws and decisions that eventually made this nation a more humane and equitable place for all people, not just white male property owners.

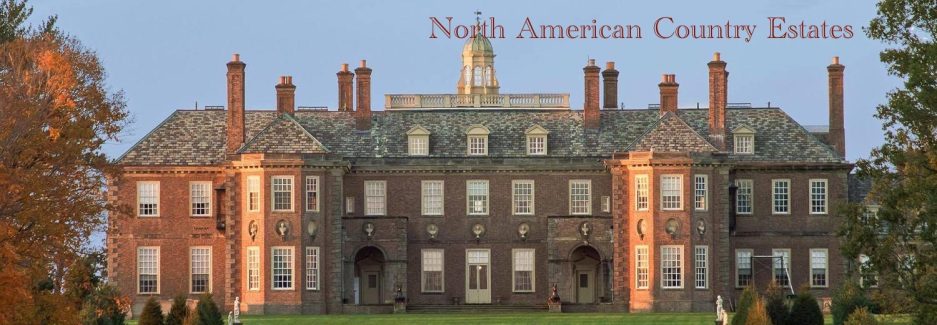

Monticello got its start when Jefferson inherited a 5,000 acre tobacco plantation outside Charlottesville from his father in 1757. Jefferson started working on plans for a plantation house right away but constantly tinkered with the design, built, tore down, and rebuilt and the house was not completed until 1809, nearly fifty years after starting. Even then, Jefferson, a serial remodeler, kept tweaking the house right up until his death. During Jefferson’s service in Europe in the 1780s, he became familiar with the latest architectural trends and the work of 16th century Italian architect, Andrea Palladio, who modernized greek and roman architectural forms for contemporary designs. Jefferson adapted these ideas to Monticello and the result is the handsome 11,000 square foot neo-classical home that we see today.

Jefferson retired to Monticello after leaving public office in 1809. By this time, Jefferson was hugely famous and had hundreds of friends that visited his mountain-top estate. The cost of all this entertaining added up and the proceeds from agricultural operations on the plantation were insufficient to balance the books. Financial problems were compounded by debts that Jefferson’s wife, Martha, inherited from her father. Jefferson attempted to increase profits from ventures like a nail factory but when he passed away in 1826 (50 years to the day of the declaration of independence), he was $18,000 in debt (about $600,000 in today’s money). His daughter and sole heir was forced to sell Monticello and 500 acres in 1831 to a local pharmacist at a fraction of its value and she also parceled off and sold much of the agricultural land.

Three years later, Monticello was flipped to a Navy admiral and real estate investor, Uriah Levy of New York. Mr. Levy was a big Jefferson admirer and hoped to preserve Jefferson’s legacy. Admiral Levy spent the next 26 years preserving and restoring Monticello and using it as a summer home. He also set out to purchase the surrounding agricultural parcels and reassemble the historic estate. Admiral Levy died in 1862 and willed Monticello to the federal government for use as an agricultural school. However, because the Civil War was raging at the time the government turned down the donation since Monticello was in Confederate Virginia. The Confederacy seized Monticello as “enemy property” and then sold it. After the Union victory, Admiral Levy’s executors recovered Monticello but it was then subject to probate lawsuits by 47 different claimants who all thought they should take ownership.

Finally, in 1879 Uriah’s nephew, Jefferson Monroe Levy of New York, settled the suits and bought out other Levy heirs. By this time, Monticello, vacant for nearly 20 years, was in a sorry state. The bottom floor of the future UNESCO World Heritage Site was being used by caretakers as a barn for cattle, grain was stored on the upper floors and the grounds were overgrown. Mr. Levy evicted the caretakers and the cattle and set to restoring Monticello to its former glory. Like his uncle, Jefferson Levy was also a real estate investor and also practiced law and served in the U.S. House of Representatives for three terms representing New York State. He lived at Monticello part of the year and welcomed the tourists who had started to visit the mansion in growing numbers in the latter part of the 19th century. He also purchased an additional 500 acres that had been part of the historic estate.

In 1923, after nearly a century of Levy family ownership, Jefferson Levy sold Monticello to the newly formed Thomas Jefferson Foundation for a half million dollars and the Foundation continues to operate the estate to this day as a house museum showcasing Jefferson’s life and times. The Foundation has assiduously restored Monticello to how it would have looked during Jefferson’s life right down to the plants that would have grown on the grounds and gardens. In fact, the gardens at Monticello are world renown in horticulture circles for the rich diversity of plant material, much of which was introduced to the estate by Jefferson himself. The estate now comprises 2,500 acres and retains the form of an early 19th century country estate. Other than the vans carrying tourists to the home and their smart phones, Jefferson wouldn’t notice much difference if he was alive today.

Click here for further information about Monticello or here for a symphonic YouTube video about the estate.