In the early decades of the 20th century, the business and financial elites of San Francisco built country estates south of the city in San Mateo County in a similar manner that wealthy New Yorkers built on the Gold Coast of Long Island or Philadelphians migrated to the Main Line. Upscale peninsula towns such as Hillsborough are a modern day evolution of this development trend. Most of these estates have since been subsumed into the suburban development that occurred after World War II or have been torn down to make way for development. A few of these estates still retain an element of their bucolic past such as Filoli in Woodside or the nearby Phleger Estate (click here for more on Phleger). A little further south stands another relic of this time period, Villa Lauriston in Portola Valley.

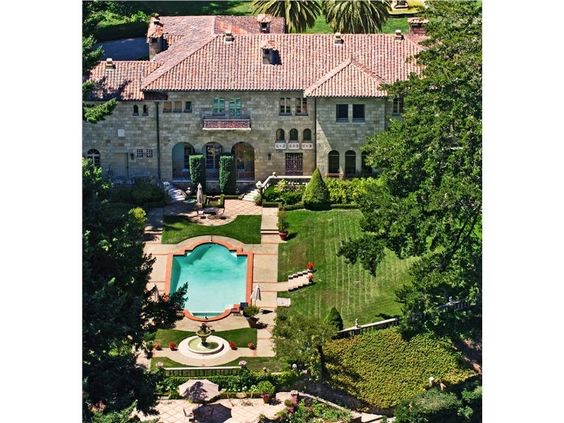

Villa Lauriston was the creation of Herbert Law, an Englishman by birth who migrated to San Francisco by way of Chicago. Herbert and his brother, Hartland, were wheeler dealers of the first order and traded in San Francisco real estate including buying the Fairmont Hotel a few days before it was damaged in the 1906 San Francisco earthquake. But their biggest innovation was starting the Viavi Company which peddled homeopathic medicines which were supposed to enhance the health and libido of women. Using the proceeds from his medication and real estate businesses, Herbert engaged architect George Schastey to design his estate. The result, completed in 1926, was the 16,000 square foot, Florentine-style Villa Lauriston which sat on a 1,000 acre estate in Portola Valley. During prohibition, Villa Lauriston was used as an illegal stash for all the liquor and wine that had been removed from Mr. Law’s San Francisco hotel properties. Herbert lived at the Villa with his wife, Leah, and their daughter, Patricia, for 11 years.

The story of Patricia is a sad one. Raised by nannies, educated at home by tutors and then at Stanford University, her parents started building a separate grand villa on the estate just for her when she was only five years old. In a macabre twist of the Cinderella legend, the manor-born, Stanford-educated Patricia fell in love with a gas station attendant, also named Stanford, in 1942 and much to the consternation of her parents married him while she was still in school. He then shipped off to the Pacific to fight the Japanese as a U.S. Marine. Perhaps as a result of parental pressure, Patricia divorced Stanford as soon as he returned from the war. One month later, Patricia was discovered, asphyxiated, in her car with a garden hose running from the exhaust into the car’s interior. Next to her was a couple of books. Apparently, she decided to do some reading while she drifted off into eternal sleep. Patricia’s unfinished villa slowly fell into ruin and burned in 1971.

The Laws sold Villa Lauriston to John Neylan in 1937. Mr. Neylan was the personal attorney for William Randolph Hearst (of Hearst Castle fame), was on the Board of Regents for the University of California for 27 years and was a member of the Bohemian Club, one of those secretive, ultra-exclusive organizations dogged by conspiracy theories that they secretly run the world. While associated with the UC, Mr. Neylan promoted the career and vision of the nuclear physicist, Ernest Lawrence, who founded Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. Legend also has it that Mr. Neylan burned all of W.R. Hearst’s personal papers at Villa Lauriston upon the publisher’s death in 1951 – much to the consternation of Mr. Hearst’s enemies, creditors and biographers. Mr. Neylan lived at Villa Lauriston for many years before passing away in 1960. His heirs apparently struggled with Villa Lauriston before selling the estate to a group of investors in 1969. These investors dedicated most of the estate’s woodlands to conservation and subdivided the rest to carve out a couple of other residential properties leaving Villa Lauriston with about 29 acres.

After 1970, Villa Lauriston changed hands a couple of times. A sleazy commodities dealer held it for a while. Then a Silicon Valley tech entrepreneur named Norio Sugano bought it for $3.7 million. This latter day history of the Villa is an object lesson in the sheer cost and difficulty of maintaining such extravagant homes. Mr. Sugano had similar luck as the previous owners and the home was forced into foreclosure in 2012 although he did add a vineyard for growing wine grapes. It was sold at auction in 2013 for $13 million after being listed for as much as $20 million. The current owner is reportedly Eric Schmidt, the former CEO of Google.

The story of Villa Lauriston points out the difficulty of owning such large estates. On the other (more civilized) side of the Santa Cruz Mountains, much smaller, more manageable estates in Woodside sell for $20 million plus and find takers. There is a subset of wealthy individuals and families willing to take on the management of a large country estate but it can become a full-time job and the subset isn’t a big fraction of the home owning public. Fortunately for the nation’s architectural heritage, people like Mr. Neylan, Mr. Sugano and Mr. Schmidt step up and preserve these priceless (or just hard to price) homes. For those interested in more info on Villa Lauriston, an entertaining video is available on Youtube here or you can click here for a Youtube video with some more history on the house and those lived in it.

Oh….if you want to buy some of Mr. Law’s medicines, you still can. Viavi Company still exists at http://www.theviavicompany.com